Cut Read online

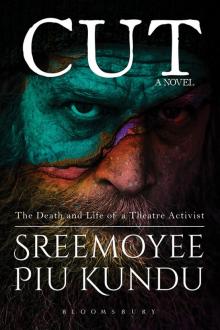

CUT

The Death and Life of a

Theatre Activist

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu

Praise for the Author:

Status Single

‘The private lives of Indian women are rarely seen as worthy of public discussion – the government censor board last year briefly banned a movie about four small-town women because of its ‘lady-oriented content’ – so the stories in Kundu’s book read as bracingly frank.’ Los Angeles Times

‘…a wide-ranging and searing attack on the Indian patriarchy...’ TSG, The Sunday Guardian

Sita’s Curse

‘A haunting treatise on female physicality, strength and self-discovery... ’ The Hindu

You’ve Got the Wrong Girl

‘Sreemoyee Piu Kundu’s perspective is unconventional, her language is poetic and sensuous, the humour is highbrow and the narrative is replete with originality and philosophical ponderings on life, love and their mysteries…’ The Pioneer

Books by the Author:

Faraway Music

Sita’s Curse

You’ve Got the Wrong Girl

Status Single

BLOOMSBURY INDIA

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No. 4, DDA Complex, Pocket C – 6 & 7,

Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY INDIA PRIME and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in India 2019

This edition published 2019

Copyright © Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, 2019

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu has asserted his right under the Indian Copyright Act to be identified as the Author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

ISBN: 978-93-88271-58-5 EBook: 978-93-88271-60-8

Created by Manipal Digital Systems

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc makes every effort to ensure that the papers used in the manufacture of our books are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. Our manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

To

Basudev Kundu

November 18, 1948

Dear Baba

For your 70th birthday.

I’m sorry we took so long to become friends.

I know, like me, you wanted to own your own sky.

Paint it in your own colours.

Pick your own stars.

Describe the sunsets you longed for.

Thank you for this life.

I love you. I set you free.

Contents

ACT ONE:Mī Jivanta Ahē (I Am Alive)

AMITABH KULASHESHTRA, 2002

THE HINDUSTAN

MAYA SHIRALE

AVIK DASGUPTA

RK CHOPRA

SARLA KULASHESHTRA

MAYA SHIRALE

AVIK DASGUPTA

RK CHOPRA

SARLA KULASHESHTRA

ACT TWO:Blindside

MARIE BOURDAINE

SARLA KULASHESHTRA

MARIE BOURDAINE

SARLA KULASHESHTRA

MAYA SHIRALE

AVIK DASGUPTA

RK CHOPRA

SARLA KULASHESHTRA

ACT III:CUT

AVIK DASGUPTA

MAYA SHIRALE

RK CHOPRA

MAYA SHIRALE

SARLA KULASHRESHTA

AVIK DASGUPTA

MAYA SHIRALE

AVIK DASGUPTA

MAYA SHIRALE

Acknowledgements

About the Author

ACT ONE

Mī Jivanta Ahē

(I Am Alive)

AMITABH KULASHESHTRA, 2002

The train pulls out of the station as I clamber on in a daze. My mind is abuzz, a million voices racing through it at the same time. Droplets of sweat trickle down my face as I push my way inside the cramped compartment.

Someone – who are you, dammit? – speaks in my head. Insistently. Where are you going this time? Have you informed anyone of your leaving before setting out? What are you hoping to achieve? Here? In this crowded station thronging with the sweat of human traffic?

The train pulls away. Everything grows distant; blurred. Far away, I see the dirty cement bench I had shared with a man and his monkey, buying bhajis for the three of us with a ten-rupee note, the last in my wallet.

The voice is back, growing louder, shriller, matching the commotion inside: Haven’t you burnt enough bridges? Does the murder of your colleague and the acquittal of that hateful man not haunt you enough? Can the professional, high moral ground you took justify your personal mistakes? The friends you walked away from? The women you let down? So, you want to make amends now? Can a man ever direct the course of his own life? Is it that simple, ever?

I place my hands over my ears. The voice never stops; a monster that taunts me; revels in my follies.

I won’t succumb to it. I have no one left to hurt now. I am a shadow. A story that has been told.

An end without a beginning.

A corpse in a casket.

A life exhausted of purpose.

An afterthought.

I grab the iron railing, jostling to my left, desperate to steady myself. The faded cloth bag I am carrying slides off my shoulder. My eye is caught by the intricate gold work on a lady’s yellow sandal. My face is flushed from the unrelenting June heat.

‘Ticket, tickat!’ I hear the words from a distance, the din growing thicker as more passengers hurriedly scramble on to the bogey from other compartments. I am out of breath. A lady in a gaudy purple net sari elbows me viciously, making her way ahead.

I am sweating profusely. Clutching the cloth bag to my chest, I peer through the window at the man holding up a brass ring, running alongside the train, faster, faster. The madari, the monkey-man, widens his eyes and is saying something, gloating, as if at the challenge that suddenly poses itself.

Man vs. Animal.

‘Tick-at...!’

A crippling pain pierces my chest. I lurch to the ground as the bag slips from my hands. I feel my body painfully slumping near the window. I try to remain focused; to not lose sight of the monkey; at the same time to not let go of the bag…

‘ Tikīta kōthē āhē? (Where is your ticket?)’ I lip-read, as a pot-bellied man in a khaki cap thumps my chest roughly.

‘My bag…the ba…’ my throat is completely parched.

‘Looks like he doesn’t understand Marathi! And why is he lurking around the seats reserved for us?’ A woman sniggers; poking me under my armpit.

‘Hey, you, what’s your name? Yes, you?’ I swerve, as the ticket-collector grabs my collar, trying to haul me up, his sour breath engulfing my face. I cover my nose, my temples throbbing.

Where...where is the...where is the monkey? It’s all happening too fast, jump, jump...you can...you can do it, c’mon, jump…it’s simple…all you have do is raise your feet and…concentrate…can you hear me? There are always voices…so many of them…

I reach agitatedly for the iron rails: ‘Where is my bag? That’s my…it has everything…’ I manage to hoist myself up, my hand accidentally touching the woman’s heaving cleavage, the skin around it moist, tense.

Just then the monkey soars into the air as the station passes away at breakneck speed. ‘Thamba! (Stop!)’ I scream, the veins on my neck protruding; pools of saliva collecting in the corners of

my mouth. The sharp pain returns. I sink down on my haunches. My spectacles fall, shattering. I stretch out my hands, groping, grasping…

Someone kicks me hard in the pit of my stomach.

‘Bastard, touching ladies in an indecent way? Is this why you boarded the train? Just who do you think you are? What bag, bag, huh? Bloody pickpocket…lecherous old man…’

‘What’s in that bag? Bomb?’

A motley crowd of women assembles, their eyes mean, each face more menacing than the next.

‘What’s your name? Yes, I am talking to you, mister!’ A woman demands, her heavy, heaving bosom, rising and falling.

I cover my eyes, unable to bear the excruciating chest pain that has returned with redoubled intensity.

‘Madarcho…’

‘Amitabh, Amitabh, I think…I’m not sure…I can’t be sure…’ I falter, the air sucked out of my lungs.

‘Tick-at….’

‘What are you doing here? Don’t you know these seats are specifically reserved for women? Can’t you read, you halkat!’

I blink a couple of times, my face dripping with sweat, trying to form a full sentence, wondering if someone has nicked my bag. My vision clouds…

There is Ammi, freshly bathed, her hair loosely knotted, her skin doused, dewy. Kneeling on a frayed prayer mat, reciting the Kalma. Her fine lips opening and closing as I study the movement of her slanted mouth through a transparent curtain…

‘Randechya! (Son of a bitch!)’

‘Maar thyala!(Hit him!)’

‘Pickpocket!’

‘Eve-teaser!’

My unmoving eyes dimly register the minuscule beads of perspiration trickling down the woman’s ample cleavage. I clamp them shut, imagining her parted plump lips slowly settling over mine…

Sarla, as we made love, that night, minutes before I exploded inside her, lolling back her head, in languorous slow motion, her moans multiplying. The rains, unrelenting, outside our home in Pune…the sky a pensive purple. The scent of the fresh mogra flowers that she carefully entwined in her thick plait, permeating the stubborn stillness between us...

‘Pervert.’

‘Bastard.’

‘Beggar.’

‘Stupid.’

‘Stupide, not stupid…’ Marie burst out giggling when I asked her if I could kiss her. Calling me ‘stupide’ several times as we sipped on red wine straight out of a bottle, sitting cross-legged on a fancy, four-poster bed. Some of it splattering onto the clean white sheets as we leaned over, kissing clumsily, for the first time…Marie gently rubbing her pink, pointed nipples, her slender fingers etching porous patterns on her pale skin…

‘Shall we pull the chain?’

‘Think he’s dead?’

‘What if he’s really carrying a bomb, or something? What if he is an atankvadi?’

‘Terrorist?’

‘Anti National?’

‘Pakistani?’

‘Same difference.’

I lay still, not responding. Sprawled out in the dirt.

Mrinalini, stubborn, sullen, way more arrogant than girls her age; didn’t speak to me for days when I yelled at her for muffing her lines, calling her ‘muka’, dumb, in Marathi. Her dark, doe-like eyes had brimmed with tears but her back was held straight. Her face betrayed nothing. Standing tall, even as I flung the script at her. The look of scorn on her face…Like she wanted a fight…

My body is inert; but my mind is everywhere, at once, scrabbling at memories, at the moments that defined my life.

That made and then unmade me…

‘Put your hand on the Bhagwad Gita and swear you will speak the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth…’.

The Sessions Court where my case was being tried was packed to the brim. At the back of the cramped hall stood a long line of press photographers and television camera crews; their flashlights pointing directly at my eyes, the intensity of the flickering red spots no different from the automatic rifles that the Rashtriya Dal goons had aimed at my troupe, in Malegaon. Prakash Lele, my leading man had stood between me and the mob, as Amol Rawat labelled me a Congress puppet. I think he used the word ‘najais’. Prakash, who lost his life, defending me…

It was just after the Mumbai riots in 1992. Amol Rawat’s words rang in my ears: ‘Didn’t I tell you to stop brainwashing these illiterate villagers? This play of yours is a bloody catalyst…politically motivated…what are you trying to tell them, huh? Teach this ignorant lot? That Muslims deserve equality…? That Hindus started the riots in Mumbai…? That we have blood on our hands? That the Koran is no different than the Gita? Eka vesya mulaga (son of a whore) have you even read the Gita to know the difference?’

‘Why the Gita?’ I had asked in court, my forehead smarting from the stitches. ‘Why the Gita? Why should I swear on the Gita that whatever I am saying, is the absolute truth?’ I took a deep breath, adding slowly: ‘Why not the Koran or the Guru Granth Sahib or the Holy Bible – why in a so-called secular country, must there exist this blatant form of subversive, identity politics? If I killed a man and touched the Gita and said I didn’t – would that absolve me of my sins?’

The judge banged the table with his wooden hammer.

I grabbed the rails with my unbandaged hand and continued: ‘I am a director of plays, your honour, a writer and a performing artist. I have no religion except my conscience. My atma is infinite. It belongs everywhere. I did nothing wrong in staging the play – I am as much the son of a Muslim trapeze artist, as I am of a staunch Maharashtrian woman, as I am of a cheap whore. All three were the same woman from whose womb I was birthed. I grew up in a travelling circus, slept beside the animals and shat in the same place where they defecated. The water I bathed in was the same that was used to quench their thirst on sultry, summer nights. The stage where my father, a blind clown, performed his legendary acts, was the same where young, underweight children hung precariously from coir ropes, and well-fed lions were tamed by starving men lashing thick whips, where everyone followed a mundane drill, where colourful clowns danced to the same songs every evening and where stuntmen in fake leather jackets astride noisy motorcycles balanced themselves precariously on one leg.

‘What if that circus is my country, my lord? What if my country is my conscience? What if the poor have no religion? Except to survive? To clothe their bare backs and feed their naked children? To just live out another day? What if our nationality, our religion, our gender, are all man-made concepts? A convenient construct to make people conform? Follow someone you can’t see or fight? What if religion wasn’t a loaded gun? A veiled threat? An election ticket?

‘What if you all killed him – killed my comrade, Prakash Lele? If everyone present here must shoulder the blame for his bloodied death? What if we all failed her? The Muslim girl who loved the Hindu boy, who wanted nothing more than an ounce of personal freedom and the dignity of choice? Whose prayer was penance…’

Amol Rawat’s lawyer cut in harshly: ‘Please, this is not a street play, here. You will be asked certain specific questions on the basis of the police case filed by the State in the light of the alleged murder of Prakash Lele, who was trying to save you, by the way.’

‘Prakash saved my life and lost his own, yes, but we were trying to save something bigger, much bigger; we were not fighting a pitched battle, but a dangerous war. A war that is more than this…all this…that will not end with his unfortunate death…’

‘You have levied a murder charge against Amol Rawat, but the court holds you guilty of inciting communal violence yourself. Sedition…do you even understand the meaning of that word, the severity of it…huh? There is a sedition charge against you, Mr. Kulasheshtra. Conduct or speech, inciting people to rebel against the authority of a state or monarch…Why stage a political play in this hypersensitive environment…?’

‘I am aware of the sedition law…incorporated into the Indian Penal Code in 1870 as fears of a possible uprising made the colonial authorities uneasy. Sect

ion 124-A…that is now being misused to browbeat anyone who protests, or put forward an alternate discourse, or speak in a separate vocabulary – into a mute compliance…a sign of a cowardly, spineless and oppressive state willing to use any methods to intimidate dissenters. How long can you do this? Criminalize dissent? Tribals resisting displacement…villagers who resist a nuclear project…student leaders in premier institutes…Muslims cheering for a rival nation in a cricket match…cartoonists…satirists…academicians…historians…anyone who advocates on behalf of the marginalized and displaced communities…how many more voices will you silence? For how long will you hide behind an archaic law that has lost its relevance, and in doing so, surrender the democratic legitimacy of our nation…forge a new and sinister ideological blueprint?’

Rawat’s lawyer jumped up: ‘I fail to understand what your politics is, Mr. Kulasheshtra. Fighting for the starving farmers? Defending defunct trade unions? Flying off to Paris to sleep with some famous French starlet, not to forget your romantic fiasco in Mumbai…? My lord, this is a man of loose, wavering morals, who courts controversy to gain footage in the media…he is in no way the saint he portrays himself to be,’ the counsel for the defence thundered.

‘What if sedition means taking a stand, my lord? What if there is another formula of freedom? What if there are no flags, my lord? Or kingdoms left to conquer…or swarthy, skin-and-bone slaves to take captive? Conquer? Colonize? Castigate? Castrate? What if we don’t go to war, outside? If the war now flows in my veins, my lord? What if the revolution that we all fear so much, will be fought by artists? By ordinary commoners. By rank outsiders. The have-nots. By an ugly, poor fellow, who stays hungry all night? Who writes stirring poems in the last light of the setting sun? And performs somersaults casting oblong shadows on the street pavement? The man who carries no weapons. Wears no uniform. Who doesn’t need a passport. The man who has nowhere to go. The man who goes nowhere. The kalakaar. The kavi. The kissan. What if he is here, in this Sessions Court, today? Looking into the eyes of a fascist dictator?’

Cut

Cut